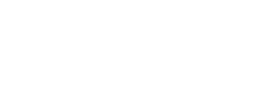

Jewish communities in Crete have existed since the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE when Jews from Eretz Israel/Palestine and Egypt first established settlements on the island (and elsewhere in Greece) following the conquest and Hellenisation of the Near East by Alexander the Great. Thus, they constitute one of the oldest diaspora communities in the eastern Mediterranean and are called Romaniote Jews. The term ‘Romaniote’ refers to those Jews who trace their origins to the Hellenised, Greek-speaking Jews of the Eastern Mediterranean in the Roman/Byzantine and Ottoman Empires and the subsequent nation states that emerged in those territories. Romaniote Jews developed a distinct liturgical tradition and spoke ‘Yevanic’, a Judeo-Greek dialect infused with Hebrew loanwords and written in Hebrew script, and Romaniote synagogues like Etz Hayyim have a distinctive interior layout. The history of Cretan Jews can be traced in ancient inscriptions, medieval manuscripts and other written and archaeological sources, as well as Etz Hayyim Synagogue in Hania, today the only remaining testament to their presence on the island.

The History of the Jews of Crete

The Hellenistic Period (c. 3rd to 1st centuries BCE)

The Jewish presence in Crete dates from the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE when Jews arrived from Egypt, perhaps part of Egyptian military campaigns, and from Palestine during the Maccabean Revolt. These early communities were Hellenised, that is, culturally Greek. It was for these and other communities which no longer spoke Hebrew that the Bible was translated into Greek, the so-called Septuagint.

.

Jewish communities on Crete are first mentioned in 4th century BCE epitaph inscriptions from Kassanoi and Kissamos. In Kissamos, a “Sophia of Gortyna, an elder and leader of the synagogue”, is mentioned and attests to the leading role of women in diaspora communities. A community in Gortyna is described in the First Book of Maccabees (15:23) dating to around 142 BCE. Gortyna was the most prosperous city on Crete during Hellenistic times.

.

Although only fragmentary inscriptions remain in Crete, inscriptions dating to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE from an ancient synagogue on the island of Delos honour two citizens of Heraklion and Knossos. This indicates the prevalence of a Samaritan community in Crete and also makes the existence of a Jewish community there quite likely.

The Roman/Early Byzantine Period (1st century BCE to 9th century CE)

By the time of the Roman conquest of Crete in the 1st century BCE, Jewish communities were thriving in most of the major cities including Gortyna, Kissamos, Hania, Rethymnon, Knossos and Sitia. According to Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria, the larger Greek islands including Crete were “full of Jewish settlements.” In the 1st century CE, Roman historian, Tacitus provides an intriguing theory regarding the origin of Jews. He claims that the Jews were, in fact, Cretans and that their original name was “Idaeans” (in other words, “from Mt. Ida”). Beyond the obvious etymological similarity, his theory may also be based on part of the tradition linking the Philistines to the Eteo-Cretans who were fleeing the island following the arrival of the so-called Sea Peoples ca. 1200 BCE.

.

Jewish communities in Crete are also referred to in the New Testament Acts of the Apostles as having been present at Pentecost in Jerusalem (2:11). Equally, the Letter to Titus provides an indirect testimony to the Jewish presence in Crete. Jewish historian, Josephus Flavius states in his autobiography that his second wife came from Kissamos. He also describes how an impostor claiming to be Alexander, the son of King Herod, gained a following, as well as financial support among Cretan Jews in the early 1st century CE. A second messianic fervour captured Cretan Jews in the mid-5th century CE when Moses of Crete, a self-proclaimed Messiah, spent a year travelling around the island proclaiming to be the same Moses who had led the Israelites through the Red Sea and into the Sinai. He promised that in the following year, he would lead Crete’s Jews to the Holy Land. Commercial and economic interests were abandoned in anticipation of that miracle and on a specified day, the Jews of Crete met together and, to the horror and amazement of Christians watching the event, threw themselves off the cliffs and into the sea. Many individuals drowned; still others were saved by fishermen assembled in nearby boats to watch this unfolding episode. Recounting this event in his Historia Ecclesiastica, Christian historian, Socrates Scholasticus claims that there was allegedly a general conversion to Christianity on the part of the survivors. This episode took place during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (408-450 CE). During his rule over the recently Christianised empire, Jews were singled out for prohibitive legislation. Jews of Egypt and Palestine especially bore the brunt of a wave of anti-Jewish sentiment that, among other aspects, led to restrictions on the building of synagogues, closure of rabbinical schools and the abolition of the office of Nasi (Patriarch). After the fall of the Roman Empire in the West in 476 CE, Roman rule continued in the eastern part of the empire (later termed the Byzantine Empire) where its citizens continued to view themselves as “Romans”, a term that should eventually be associated with the Greek-speaking Jews, the Romaniotes. At this time, Crete was one of the 64 provinces of the Byzantine Empire with its capital in Constantinople, the prevailing seat of the Greek Orthodox Church. Crete remained part of this empire until the Arab invasion of the island some five centuries later.

The Andalusian-Islamic Period (825-961 CE)

In 825 CE, Byzantine rule of Crete was interrupted by a short-lived Arab take-over and occupation of the island for which there is scarce archaeological and archival evidence. Crete was seized by Muslim exiles from Andalusia who established an emirate across the island from their base in what is now the city of Heraklion. Out of its port sailed corsairs or pirates who launched shipping raids throughout the Aegean. Athens was apparently attacked, if not occupied, for a period of time and Thessaloniki was also seized and sacked during one of these attacks. For the first time in over 2000 years, Crete once again became a thalassocracy amassing wealth through periodic raids of the coastal cities throughout the eastern Mediterranean. At this time, both Heraklion and Hania were surrounded by a great moat and fortifications. Even though Jews are not mentioned in the extant historical accounts for this period, it is most likely that they were active in the island’s urban centres. Their community was well-established in Heraklion by the 11thcentury following the re-conquest of the Crete by the Byzantines in 961 CE.

.

The Late Byzantine Period (961-1204 CE)

Crete was again part of the Byzantine Empire following the successful Byzantine re-conquest of Crete in 961 CE. Just like for the preceding Islamic period, archival and archaeological evidence for the Jewish presence on the island is scant for this time. However, Jewish communities in Crete likely continued to thrive given the abundance of historical material on Crete’s Jewish population during the course of the next major epoch of Cretan history, the Venetian period. During the late Byzantine times, Jewish communities were not permitted to live within walled, fortified cities, but rather as close as possible to the main city gates for protection in times of danger. The proximity of the Jewish quarter – documented for the Venetian period – to the main gates of the city of Hania, for example, suggests that the location of the Jewish quarter may date to Byzantine times or even earlier. In 1204 CE, the sacking of Constantinople by the 4th Crusade effectively led to the temporary dissolution and long-term weakening of the Byzantine Empire. Crete was then sold to the Venetians by the Marquis of Montferrat, the leader of the 4th Crusade, who had been given the island as a gift.

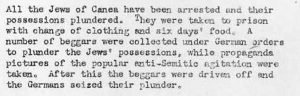

The Venetian Period (1204-1669 CE)

Venice purchased Crete in 1204 and like every foreign ruler before them, the Venetians coveted Crete as a base that offered protection for their navy and from which they could control the eastern Mediterranean trade routes. As one of their most important colonies, Regno di Candia (Kingdom of Kandia) with its capital at Kandia (Heraklion), the island also provided valuable agricultural resources which could be traded. Venetian authority was heavily contested in the first century of Venetian rule by the Cretan population due to heavy taxes, land confiscations and other measures including the prohibition of the Greek Orthodox Church and its hierarchy on the island. In spite of these hostilities, however, Venice encouraged its citizens to colonise its various outposts around the Mediterranean, especially Crete. Approximately one-sixth of the Venetian State’s population, or 10,000 people, migrated to Crete during the first sixty years of Venetian occupation. By the 16th century, the three main cities of Kandia (Heraklion), Retimo (Rethymnon) and La Canea (Hania) were flourishing, the island’s population swelling as a result of an influx of new immigrants and its economy thriving due to trade and trans-shipment business. Crete produced and exported Malvazia wine, grain, olives and olive oil, cheese, cotton, silk, acorns used for tanning, honey, wax, citrus fruits, timber and salt. Venetian domination of the island continued for 465 years until the Ottoman Turkish invasion of Crete that began with the two-month siege of Hania in August 1645, and ended with the conquest of Heraklion in 1669 after a 22-year siege, the longest siege in European history.

.

Cretan Jews maintained already established urban communities in the three major cities, as well as in the more rural settlements at Milopotamo, Castelnuovo, Castel Bonifacio, Belvedere and Mirabello. They numbered about 1,600 by the end of the 16th century. Heraklion, the centre of Jewish life on Crete at the time, had about 800 Jewish inhabitants and a total of four synagogues. In the main cities, Jews were required by the Venetians to live in segregated ghettos or quarters called Zudecca that were locked at night. They apparently had to wear a yellow cap or badge on their external dress in public, signs were displayed on the doors of their houses and they were excluded, with few exceptions, from participation in the local administrations. The Venetians, later during their rule, issued a further number of restrictions that effectively banned, or at least severely curtailed, the interaction between the island’s Jews and Christians, both Catholic and Orthodox. Jews were prohibited from eating, drinking or gambling at Christian-owned taverns and employing Christians in their work and households.

.

According to Venetian accounts, Crete’s Jewish community grew significantly over the 14th and 15th centuries due to the influx of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula following the exodus of 1391, the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and again in 1492 from the Iberian Peninsula. Hania, in particular, attracted new Jewish settlers from Spain and Italy, as attested by the names of some of the city’s prominent Jewish families including Zeroycho, Astruc, Franco and Spagnuol from Spain, and Balaza, Verzo, Barbeta, Balliaza and Sacerdotto from Italy. It seems that these and other immigrant families were absorbed into the indigenous Romaniote communities through the adoption of the local language, culture and religious customs, as well as intermarriage. Apart from those urban communities on the island, the small rural communities produced kosher cheeses, wines, grains and etrogim (citron) for both export and local use. Laws were subsequently enacted to prohibit Jews from making further purchases of land in order to restrict Jewish competition in rural commerce and agriculture which forced some of the community into money lending, together with the trade of silk, metals, dyes and leather. Jews with less capital worked as grocers, artisans, tanners and butchers. They were also active in intellectual pursuits including philosophy and theology and many individuals travelled widely, especially to Italy to places like Padua and Mantova for schooling where they trained as doctors, lawyers and rabbis. Such well-known Cretan Jewish intellectuals from this period included members of the Balbo, Capsali and Delmedigo families.

The Ottoman Period (1669-1898)

The Ottoman Turks conquered Crete between 1645 and 1669 for the purpose of controlling the trade routes and exploiting Crete’s valuable agricultural and commercial resources much like the Venetians before them. Having first captured Hania in 1645, they set about converting all but one of the Greek Orthodox and Venetian Catholic churches into mosques, baths and bakeries. They more or less maintained the defences, and began a large-scale building scheme where new structures including mosques were built and older Venetian structures renovated and refurbished. Yet, at the same time, the first century of Ottoman rule in particular brought many hardships on the Orthodox Cretans such as heavy taxes, mass evictions from the cities, emigration and executions. Many Christians converted to Islam to chiefly maintain and protect their material privileges and rights which was a phenomenon that continued throughout the entire period of Turkish rule. Town life was devastated and the island’s economy shrank to an elementary form of agricultural and pastoral life with grain, legumes and salt the most common exports. With the exception of the first decades of occupation, very little of this money was reinvested and as a result, the construction of public works eventually halted altogether and roads, harbour-works and defences fell into gradual disrepair. However, the Ottomans reinstated the Greek Orthodox Church on the island for the first time in centuries so that the state could exercise influence over its Orthodox subjects. By the 18th century, the economy improved slightly with large-scale cultivation and export of olive oil and soap, as well as smaller quantities of almonds, chestnuts, honey, wool, silk and wine and later in the mid-19th century, the Ottomans established an educational system for both Muslims and Christians for the first time on the island.

.

Despite these initiatives, however, two and a half centuries of Turkish rule witnessed numerous Cretan rebellions culminating in an almost constant struggle for independence in the 19th century. When the Greek War of Independence (1821-1832) led to the foundation of an independent Greek state in 1832 with Crete left outside its borders, Crete was briefly ceded to the ruler of Egypt, Mehmet Ali, until 1841 when it was handed back to the Ottoman Turks. This further ignited calls for Crete’s union with Greece. With heightened tensions between the Cretan Muslim and Christian populations with the latter repeatedly rising up against Ottoman authority, and with excessive violence from both sides, various attempts were made to reform the administration of the island which brought new political affiliations and institutions in which Cretan Jews were also represented. Yet, the island’s Jewish population was caught up between the contending majority groups and much like the Cretan Muslims, they did not fit the increasingly exclusive definition of Greek nationalism. As a consequence of political and economic pressure, many Jews left the island: in 1817, there were 150 families divided between Heraklion and Hania, in 1858, there were 907 Jews on the island, but by 1881, only 647 Jews remained with the majority residing in Hania. Many privileged and wealthy Jewish families moved to Venice and elsewhere in Italy and to other Mediterranean enclaves like Gibraltar, Istanbul and Salonika.

.

The Great Powers (Britain, France and Russia) remained wary of a breakup of the Ottoman Empire and thus refused to support mounting aspirations for a union of Crete with Greece. Instead, in 1898, Crete was made an autonomous republic under a Greek prince regent and a parliament was established, with several Jewish representatives who managed to claim their constitutionally guaranteed seats only with great difficulty. After Crete was formally annexed to Greece in 1913, Jewish emigration continued until only 360 Jews were living on the island by 1941.

.

Overall, the period of Ottoman Turkish rule on Crete brought economic hardship and progressive intellectual stultification for the island’s Jewish population which, over time, diminished significantly. Yet, in other ways, Ottoman Turkish authority was favourable to Crete’s Jewish communities. In towns like Hania, the former Venetian ghettos were opened and Jews were allowed to settle in neighbouring quarters abandoned by the Venetians. In fact, they were permitted to buy and legally inherit property for the first time which may have enticed Sephardic immigrants from North Africa and Izmir, as well as the return of those Jews who had previously fled to the islands of Zakynthos and Kythira. A case in point relates to the Etz Hayyim Synagogue, once an abandoned Venetian Catholic church which was acquired by Hania’s Jews from the Ottomans in the mid- to late 17th century. Crete was also drawn into a different economic sphere with ports such as Hania, Ierapetra, and Rethymnon now in close contact with Izmir, Alexandria and Benghazi. Cretan Jewish family names reflect these contacts including Constantini (from Constantin in North Africa), Minervo (from Alexandria), Mizrahi (Izmir) and other names that appear to belong to Ashkenazi Jews from Europe.

Hania’s Jewish Community in the 19th Century

In the mid- to late 19th century, the majority of Cretan Jews, by then numbering fewer than 700, resided in Hania. The Haniote Jewish community occupied the old Jewish Quarter called Evraiki, but a few affluent families moved to larger houses in neighbourhoods such as Halepa and Dikastiria around the Court House. During the 1860s and 1870s, a series of blood libels were directed against the Jewish communities throughout the Ottoman Empire. In 1873, such a case happened in Hania when, after the apparent disappearance of a Christian boy, a mob attacked the Jewish Quarter and had to be pushed back by police intervention. The boy was discovered the following day in a village near Hania. Attacks like this case were not uncommon and occurred once again in Hania in 1882 and in Heraklion in 1884. Similarly, the various dates for the burials of four rabbis in the southern courtyard of Etz Hayyim Synagogue suggest that during those periods, the Jewish community was prevented from reaching the cemetery outside the city walls due to unrest in the city, itself. In 1875, a momentous development took place regarding the civil rights of the Jewish community. The community appealed to the Ottoman imperial government, asking that a Jew be elected to the (albeit short-lived) General Assembly that had been established as part of the mid-century administrative reforms. After considerable opposition from within the Assembly, Abadaki Delmedigo was eventually admitted to the Assembly in May 1875. One of the propositions he presented there concerned the traditional burning of an effigy of Judas Iscariot during the Orthodox Holy Week. This practice was henceforth prohibited by law.

.

Another notable event in the life of Hania’s Jewish community at this time was the renovation of Beth Shalom Synagogue located on Kondylaki Street near Etz Hayyim. Beth Shalom had been built during the Venetian period and was in use by 1434, if not earlier, and apparently functioned as a Sephardi synagogue. There are no surviving records of Beth Shalom prior to the late 19th century when the community decided to have it renovated given its state of extreme disrepair at that time. The renovation was costly and was carried out under the direction of Italian architect, Nicolo Mancuso who also restored the nearby Catholic church on Halidon Street. Beth Shalom was rededicated with a service on 4 May 1880. It was in Beth Shalom Synagogue that Chief Rabbi Abraham Evlagon received King Constantine of Greece who visited Hania on the occasion of Crete’s union with Greece in 1913 and, according to custom, attended religious services not only in the Orthodox Cathedral, but also in the main mosque and in the synagogue. A photograph shows Evlagon with Rabbi Ilias Osmos viewing the canopy prepared for the king on that occasion inside Beth Shalom.

Chief Rabbi of Crete, Abraham Evlagon (1848-1933)

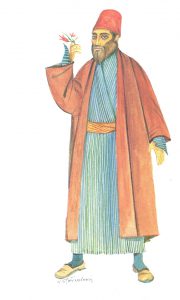

During this tumultuous period in Crete, the island’s Jewish communities were led by Chief Rabbi Abraham Evlagon (1848-1933). Evlagon was born in Constantinople and appointed in 1867 by Ottoman Sultan Abdul Aziz to steer the dwindling Jewish population on Crete though a tumultuous period in the island’s history during a time of what essentially amounted to civil war between Cretan Muslims and Christians. In daily life, however, Evlagon maintained good relations with both Muslims and Christians, as well as their heads of administration around the island and performed various services for them in a number of languages. After the semi-independence of Crete was declared in 1896, his role became increasingly difficult in a period when many of Crete’s Jews began to emigrate in large numbers and as a result, Jewish life from this time onwards was concentrated in Hania. In 1913, the island was officially annexed to Greece and Evlagon ceased to be a legally defined Ottoman appointee, although he continued his role of Chief Rabbi of Crete until his death in 1933. During the First World War, Evlagon organised assistance for Jewish refugees from Palestine who had sought refuge in Crete. Successive political leaders including Sultan Abdul Hamid, the Governor of the Cretan State and the kings of Italy and Greece decorated Evlagon for his contributions to social and political life. In 1921, Evlagon completed his memoir, both an account of his many years of service on Crete and also a collection of anecdotes and historical information for the time. He also wrote Spiced Wine that traces the series of blood libels in the 19th century and reflects his concerns about anti-Semitism and When Wine is Drunk, a collection of readings about reaching the age of 70. When Evlagon died in 1933 at the age of 88, his funeral was attended by numerous local dignitaries, together with a large crowd of onlookers who then marched in a procession led by the municipal military band around the city.

Second World War and the German Occupation of Crete (1941-1945)

The German occupation of Greece began in April 1941 and lasted until 1945. Following the failed Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940, Germany then assisted its Italian and Bulgarian allies in their expansionist aspirations and invaded Greece. Crete was attacked by the Germans in May 1941 in a major airborne campaign and the three main cities of Hania, Rethymnon and Heraklion were badly bombed. The Axis Powers were met by fierce resistance from the local population and by the Allied forces, but eventually prevailed in the 12-day Battle of Crete. The Allied troops on the island, which at some point had included a Jewish Logistics Brigade from Palestine, were forced to retreat as the Axis Powers established their occupation regime by June 1941.

.

The particular singling out of Jews by the German Military Command is illustrated by the various repressive measures implemented on German orders in the early stages of the occupation. The orders were directed to the Greek authorities and from them passed on to the representatives of the Jewish Community in Hania. A document dated 1 July 1941 was circulated to the administrations in Hania, Rethymnon, Heraklion and Agios Nikolaos that prohibited the slaughter of animals according to Jewish custom. It ordered that the knives used to this end be handed over to the island’s German Military Command, together with the addresses of those individuals who handed them in to authorities. Another document of the German Military Command, dated 23 August 1941, referred to the matter of “Jews and Jewish businesses” and ordered that a sign measuring 50 x 50 cm should be hung outside Jewish-owned businesses. The signs should read “Jewish business – Prohibited for Germans”, written in black letters on a yellow background in both German and Greek.

.

As in other areas under German occupation, the island’s Jewish population had to provide detailed lists of its members. In a letter, dated 4 August 1941, to the Mayor of Hania, the German Military Command of Crete requested that numbered lists be drawn up of “all persons of Jewish origin (regardless of religious affiliation) with names, occupation, place and date of birth, place of residence, as well as the reason for settling in Crete.” The lists were to be submitted to the German Military Command, and the Greek authorities to be held responsible for the “full and accurate accomplishment of the above task.” In a letter dated 9 August 1941, the Mayor of Hania, Nikolaos Skoulas, informed Rabbi Ilias Osmos of this requirement, asking for “as soon as possible the requested detailed list of the Jews residing in the city to be submitted to the German Military Command.” On 14 August 1941, Rabbi Osmos submitted this list with the names of 314 resident Jews. The document also noted that there were no Jews living in Rethymnon and just a few families in Heraklion. A list of Jews residing in Heraklion was requested on 2 September 1941 and later compiled, listing a total of 26 names. Jews from Heraklion were later made to relocate to Hania; the only remaining synagogue in the city was deliberately demolished by the Occupation Forces. A second community list was later requested and supplied on 17 February 1943. It listed 279 Jewish residents in the city of Hania.

.

Between 1941 and 1943, a number of Jewish individuals were executed on German orders: in Heraklion, several Jews were shot by the German Occupation Forces as part of so-called reprisals: in June 1942, two non-Cretan Jews were shot; in July 1943, all six Jewish males still resident in Heraklion were shot, along with a group of Greek Christians for alleged damage to German army installations.

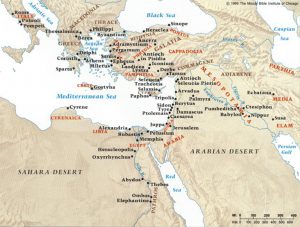

The Arrest of the Cretan Jewish Community in May 1944

On 12 May 1944, the Commander of the German Police in Athens, on orders from Himmler, notified relevant sections of the Wehrmacht that the Jews of Corfu and Crete were to be deported “with the utmost possible dispatch.” The plan included their arrest, transport to Athens and deportation to Auschwitz. The Jews of Hania were arrested on 21 May 1944 by the Wehrmacht. The SS, which normally carried out such actions with the assistance of the army, was not stationed in Crete. Those families living on Skoufon and Doukas streets in the Jewish Quarter were herded down to the harbour whereas others residing in Kondylaki and Portou streets were pushed through a narrow funnel-like passage that leads out of the Jewish Quarter at its southern end and into a small open area where trucks were waiting to load them. Other trucks had been stationed in the harbour. The eye-witness report by Katilena Singelaki describes the arrest of the community and the ensuing looting of Jewish homes. The community was then taken to the Ayias prison near Hania for 14 days during which Wehrmacht soldiers entered Etz Hayyim Synagogue and removed all religious and liturgical artefacts, books and presumably the archive of the community and dumped them into the back courtyard of what is presently the Archaeological Museum (at that time used as a military depot). The fate of the artefacts and the archive is unknown. The Jewish cemetery was destroyed at this time as well.

.

After 14 days in the Ayias prison, the community was loaded onto cargo trucks and taken to Heraklion on 4 June, where they were held in the Makasi Fortress prison for several days before their last voyage on the Tánaïs steamship that was to sail to Piraeus. The Tánaïs was built in 1907 in Sunderland, North East England, and launched in the same year under the name “Hollywood.” It was 74.5 metres long, 11.5 metres wide and 5.5m high. In 1935, it changed ownership and flew a Greek flag. Its new owners named it Tánaïs, the ancient Greek name of Russia’s Don River. With the outbreak of the Greek-Italian War in 1940, the Tánaïs was requisitioned by the Greek state and used for the transport of troops and supplies, including to Souda Bay near Hania. It was there that it sank after German bombardments at the beginning of the Battle of Crete. It was later salvaged by the German Occupation Forces and again used as a transport ship.

.

In the evening of 8 June 1944, the Tánaïs departed from Heraklion harbour heading for Piraeus with the Jewish captives on board, along with Greek Christians, who had been arrested in reprisal for the kidnapping of German General Kreipe, and Italian prisoners of war, in a convoy with three other ships. The Tánaïs was not marked as a prisoner transport. In the early morning of 9 June, the British submarine Vivid sighted the Tánaïs. At 3:14 am, two torpedoes launched by the Vivid hit the ship, which sank about 60 km northeast of Heraklion, taking with it all prisoners on board. The entire community perished onboard which effectively spelled the end of almost 2500 years of Jewish history on Crete.