The recent exhumation of fifteen burials from the former Jewish cemetery of Hania.

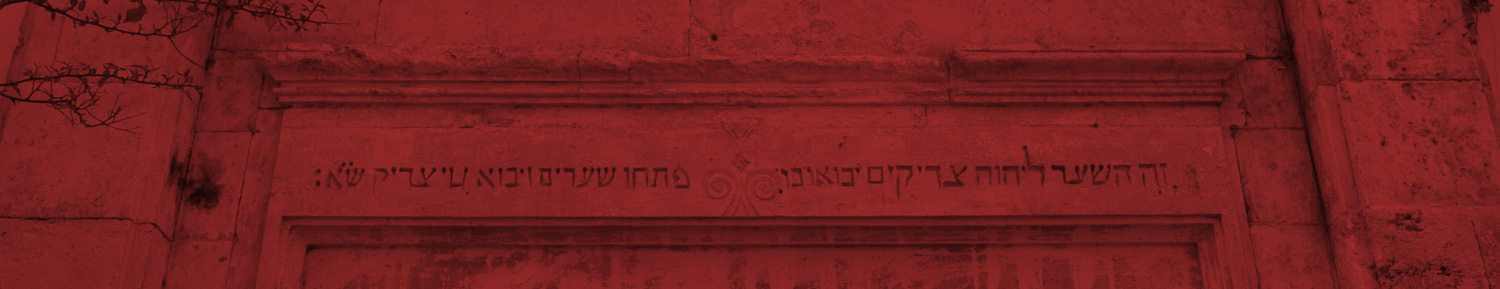

The Jewish cemetery of Hania was located in what became known eventually as Nea Hora or New ‘Area’ just beyond the 17th cent. Venetian walls and moat of the old city to the west. Access to it was either by the sea front or by a land fill in the moat that extended from one of the main fortifications known as the Lando, which is located still just at the head of Kondylakis St. which was the main artery of the old Jewish Quarter. It was also a point of convergence of two other ‘quarters’ – one Muslim and the other Christian (Greek Orthodox). The former was delineated on one side (to the east) by present day Skoufon St. which was also known as the ‘Mikri Ovraiki’ or Little Jewish Quarter and Muslim and Jewish houses occupied its length: one side being the limit of the Muslim Quarter and the other being the limit of the Jewish Quarter. The Christian Quarter – both for Europeans and Greek Orthodox was neatly snuggled in the area known as Top Hana or Cannon Foundry which was one of the main gates into Hania from the sea front. Present day Theotokopoulou St. begins at this point and at its upper end gives access to a small gateway that leads to the upper ramparts of the walls to the west but to the east follows a zig-zag course along the walls. The space between the walls and the houses is comparatively wide and also vulnerable to attack. At its eastern end it converges precisely at where the Jewish and Muslim Quarters were located and not far from it is located Etz Hayyim Synagogue which has strangely (as it is quite unusual according to Jewish Law) a small cemetery.

Recently the exhumed skeletal remains of 15 Jews were discovered in Nea Hora that have been subsequently brought to a small ‘cemetery’ at Etz Hayyim. The story is of some interest and in a sense begins with a highly peculiar Jewish burial that took place in 1821 in Hania.

It was most likely at the point of convergence of the Jewish, Muslim and Greek Orthodox quarters that in 1821 a riot occurred during the transfer of the body of Rabbi Shalom to the Jewish cemetery. Amongst the Greek Orthodox feelings were especially hot at this time since the War of Independence had broken out on the Greek Mainland and in response the Sultan had ordered the execution of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch in Istanbul as the responsible head of the Greek Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire. Very quickly news was circulated that Jews had been conscripted to dispose of the body of the Patriarch in the Bosporus (most likely the ‘Halic’ or Golden Horn) and there are recorded a good number of violent encounters in several cities and towns in Greece. In Hania it appears that it took the form of a riot during the burial of Rabbi Shalom and after several attempts to take his body for burial in the cemetery it was thrown off its bier by some young men and a decision was made by the rabbis of Hania that it be buried in the south courtyard of Etz Hayyim Synagogue. It may well have been that already a special area had been sectioned off as suitable since in the course of ‘excavating’ the south courtyard to locate the graves of R. Shalom and his brother and a student we also found the grave of Rabbi Hillel Eskenazi who had died in 1717.

In 1944, not long after the arrest and subsequent tragic death of the some 270 Jews arrested by the Nazis, the Jewish cemetery in Nea Hora was bulldozed down. Its exact limits are unknown though it had, in the course of time, been expanded to the north toward the seafront. For a good number of years after the War this wasteland of death was pillaged for its tombstones for use as building materials…either broken up for fills or reduced in ovens to lime and this process continued until well after the termination of the War. It was only after the late 1950’s that the Jewish organization responsible for Jewish communal property in defunct Jewish quarters saw fit to give the major portion of the cemetery to the city of Hania for the purpose of making it into a playground and at present a school occupies a good part of this site. Concurrent with this a somewhat ill-defined northern extension of the cemetery was sold by the pre-war president of the Jewish Community of Hania who had been in hiding in Athens and somewhat poorly built houses were built on it. By 1965 all that remained of the cemetery was a small house that had been used by the Hevrah Kedusha (now destroyed) and a plaque on the school commemorating the gift.

[nggallery id=3]In 2005 a group of Christians from Nea Hora contacted me over a matter of some concern to them. They were in the process of building an apartment building and ‘had heard’ that it was possible that the land on which it was to be built was part of the Jewish cemetery. They said that the foundations were in the process of being excavated and I asked several times if they had found any graves and the response, though negative, belied the fact that obviously they had and their concern was over what bad effects this might have had. In the end I accompanied a group of about 15 investors in the proposed apartment building to the site. Already some concrete piers had been sunk and there was no evidence of remnants in the form of either bones or fragments of tombstones. However, the fact that several in the group asked me if there were not some appropriate Jewish prayers that could be said in the event that this was an extension of the Jewish cemetery, convinced me that they had in fact found evidence that it had been. There was little that I could do other than to say a few fitting prayers from the siddur and it seemed that the incident was sealed though whenever I have had occasion to go past the completed apartment building I have often wondered about how far in fact the old cemetery had been expanded to the north.

Not long after Pesah this year a young man, Vassili Varouhakis, who works for the archaeological service of Hania came to visit us at the Synagogue. We knew him from some time before as he had on several occasions asked for help in translating some fragments of Jewish tombstones that are in the storeroom of the service. This time, however, he was very specific about a matter of some importance. An apartment building was being built in Nea Hora, the site had been cleared of several small makeshift houses that had been put up not long after the IInd World War when the president of the former Jewish Community of Hania was selling off property. In the course of clearing the site in preparation for it being deepened for the pouring of cement foundations three skeletons had been found. Of course all work on the site ceased and the skeletal remains had been determined as not being Minoan nor even of great antiquity and it had been suggested that perhaps these were the bodies of ‘gazis’ who had fought and died during the siege of Hania during its capture by Yusuf Pasha in the early 17th cent.. Their importance was becoming decreasingly so to both the excavators and archaeological service who were still holding up progress on the site, and I was once again called over to Nea Hora to see if perhaps what was suspected by some was true – that they had opened up some part of the old Jewish cemetery. On a quite hot early April noon I walked over and the first thing I noticed was elevation of the rear of the now completed apartment building that I had been called on to settle the souls of possible dead Jews in the site – some years before. Moreover I noticed on a balcony one of the little old ladies who had come with the original group. Not far behind me was in fact the northern limit of the school and its playground that had been the major and more antique site of the old cemetery. Already some excavating work had been carried out. The site set aside for the foundation work was about the size of half a tennis court and two parallel graves were pointed out to me. Behind was yet a third that still had its skeleton intact. It was more or less obvious that these were Jewish burials and I pointed out that in an area of this size that they could expect to find at least another fifteen, which in fact they subsequently did. Within a day I had spoken with Dr. Michaelis Andreanakis director of the Archaeological service, in order to alleviate all possible fears I made clear that we had no legal interest in the site nor did we concern ourselves with the question of the graves other than that their contents were ‘ours’ as under Jewish Law we were required to re-bury the skeletons with all due respect.

Several days later the area was cordoned off and a proper excavation was carried out in the course of which, as expected, two distinct parallel rows of graves were opened up adding up to a total of 15 interments. It was agreed beforehand that the contents of each grave was to be photographed and the exhumed skeleton kept intact and not mingled with the other remains. Single slabs of stone covered each grave and none had any names inscribed so each grave was given a number and the contents were to be collected in plastic bags that were to be numbered accordingly. Work was carried out quite rapidly and under the persistent scrutiny of the old lady in the apartment building opposite who apparently (I am told) with many signs of crosses and even an occasional burning of incense promised maledictions on the workers should they delay in getting the ‘Jews out’.

With the assistance of the archaeological service in Hania the skeletal remains were appropriately number in plastic bags and deposited in the Firke (Naval Museum) storerooms and after a few days Alex Phountoulakis and I went and these were emptied into numbered new pillow cases and tied securely. These were then placed in two large chests and brought to the synagogue and placed in the back garden along with the tombs of the four rabbis.

Two questions remained to be broached. One was that of whom and when the interments had taken place and the second was where exactly they were to be permanently re-interred. There appears to have been some contention between the archaeological service and the construction firm over the delays caused by this un-foreseen discovery. Once it had been determined that these were relatively recent burials and in the precincts of the former Jewish cemetery the question of appropriate responsibility had been solved but there remained a quiet serious question for us as Jews: what were the names of these people and why had there been no appropriately inscribed tombstones to mark their graves. Some of the graves had been seriously intruded into either by the digging of foundations for the now destroyed houses built after the IInd WW or by bulldozers at work on the proposed foundations of the new apartment building. A number of strange stories had already been circulating concerning what appeared to have been perfunctory burials. That the incumbents had been executed by the Nazis was one. This appeared to be of no basis as they had been given separate burials and moreover, the original corpses had been interred carefully according to Jewish practice in Greece with hand crossed over the pelvis area. What remains a mystery that we have not tried to get involved in is why there was no forensic examination of the skeletal remains if such questions had arisen.

It appears most likely that these 15 persons died between 1941-1944 and that it had been impossible, given the restrictions on Jewish practice in Hania imposed very early with the confiscation of the knives for shehita of the community shohet, to have properly inscribed tombstones set up. Most likely the plain stone slabs on top of the burials had been given some form of identification that had been erased over the years.

The permanent re-burial of the remains was a matter of some concern for us. The president of the Salonika Jewish Community said that he would be willing to send not only the rabbi but also a mortuary representative to supervise the transference to Salonika and burial there in the Jewish cemetery. With rabbinical approval we have decided to keep the remnants of these Haniote Jews in Hania, in the small cemetery next to the synagogue where there is a proper rabbinically designated limit or eruv marked by a low parapet. The two chests containing the bones will be encased in brick against the east wall of the area where rabbi Shalom, his brother and a student are buried. This in turn will be plastered and white-washed and a gilt glass copy of a Jewish burial seal from the 1st century given by Mrs. Louisa Klein will be embedded in the summit and an appropriate text from Ezekiel inscribed beneath.

N. Stavroulakis

NOTE: This endeavor is an important and significant mitzvah and was un-foreseen when making out our budget for this year. The entire cost of the erection of the brick casing etc. will come to 2000 Euros and we will appreciate any assistance from our readers.